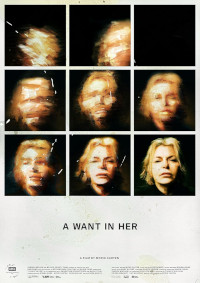

Eye For Film >> Movies >> A Want In Her (2024) Film Review

A Want In Her

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

On the phone, Myrid argues with the police in a fatigued, familiar sort of way. She explains that she saw her mother slumped unconscious on a bench with a bottle of wine, in the middle of Belfast. This much we can verify. We’ve watched through her lens as she stood there filming the unconscious woman. “Why doesn’t she do something to help her?” you might have asked yourself. Well, what? The police don’t know either. Everybody tries to pass the problem along to somebody else and every body knows, really, that the only person who can solve it is the woman herself. But does that make it okay to film her in such a state, to show that to the world?

Few things are more raw and painfully personal than the state someone gets into after years of problem drinking. The woman, Nuala, makes clear objections to the camera at times, even though she can’t frame much of an argument. The difficulty is that her suffering has never been a private thing. It has also shaped Myrid’s life, from early childhood, and to forbid talking about it would be to deny the younger woman the opportunity to explore her own pain (and, one might contend, her own dysfunction) in the way that seems most effective for her. As an artist, she has previously exhibited work on the subject. This is her first venture into film, and from a purely artistic standpoint, it’s a tremendous success.

There’s a certain grace that some alcoholics achieve after years of practice – a way of moving that’s unsteady and erratic yet rarely results in a fall, just a series of elegant corrections. It can be impressive in its way, and A Want In Her mirrors that in its form, just as it mirrors the distortions of time which develop in a drink-disordered mind. Scenes are linked by theme rather than any conventional chronology. It feels organic, spreading outwards from that centre which might swallow everything. Something in the genes, says Uncle Danny, who also feels hopeless, but for himself as well as for Nuala.

It’s not the alcohol where it begins; that’s just another symptom. mental illness runs in the family: manic depression, delusional thinking. It has brought Danny low. He lives in a caravan now, close enough to the house that Myrid’s other uncle, Kevin, can look after both him and Nuala, when she’s there. Kevin’s depression doesn’t seem to be genetic but situational. The next of kin < i>has to take responsibility, social services say. We see snippets of old home videos, an energetic younger Myrid exploring her own home. Later she would get away, escaping Kevin's fate – but never fully. Something keeps pulling her back. It’s misshapen, hard to recognise – could it be love?

She has never seen Kind Hearts And Coronets. Nuala tries to describe it – “It’s about this guy that murders all his family.”

In urban streets we see strangers going too and fro, acting out the demands of their linear lives. Out in the wild places, on the brown land, the wind whips around, the very very air refusing to cooperate. Nuala, in a more lucid moment, recalls stealing to buy drink, going to confession, going to rehab. it never stuck. It’s not Myrid’s fault, she assures her, and there’s a little bit of calculation there, awareness that she might need her, but also a hint of something sweeter. It’s not enough, Myrid tells her. The neglect that she experienced as a child can’t wholly be blamed on the alcohol. Nuala owed her something. Is this a way of taking payment?

Outside, the leaves are decaying, damp flesh peeling away from their delicate, spidery veins. Inside, there is mould on the curtains. We see old faded photographs, losing their meaning as minds decay. Nuala asks Myrid to photoshop the film so that they will all look good. In the final scene, the precarious music drops down low and we hurtle along the road, faster and faster, fleeing from something which can never truly be left behind.

Reviewed on: 09 Oct 2025